Outside it’s as though there must be two suns – one all heat, and the other all light.

On the other side of the door, however, it’s soft and cool. There’s the scent of flowers, not sprayed or plugged in, but real — fresh and bitter, dried along with their bark and leaves under just one benevolent sun. There’s a whiff too of salt and electricity, as though it’s rained recently, inside.

Dr. Claudia Sandoval looks you in the eyes, warmly, openly. You won’t feel like she’s scanning your body and your movements for places where she could tip things into balance, but it’s happening without even her thinking about it. It’s just how her eyes see now, as if they have their own consciousness. It can’t be separated from who she is, or from who you are, either.

How she got to be who she is has as many layers as the scent in the room.

Before I talked to Claudia, I laid out my questions with reference to what I know about her. She’s a native California girl, but the daughter of Mexican parents. She excelled in her 20-year career as a surgical tech, as Western as allopathic medicine gets, but she left it for a doctoral degree as Eastern as it gets, in Traditional Chinese Medicine, and now owns The Point Acupuncture and Herbal Clinic in New Braunfels, TX. From the many conversations I’ve had with her up to this point, I know she really grieves the loss of hard science as a guiding principle in public policy, but when we start this interview, she hesitates a bit with a decidedly unscientific protest – “I don’t really like to talk about myself,” she says, “I’m a Capricorn.”

I ask a lot of questions to tease these things apart, but again, even though you can see each axis — North and South, East and West, heart and mind — they can’t be separated. As we talk, it’s like watching the saturation bar move up and down on a photograph, shifting from black and white dualism to gradations in technicolor. Any contradiction one might imagine? It’s a trick of the light, depending only on your point of view.

north/south

Claudia credits her work ethic and respect for education to her parents, who emigrated to the US for better economic and social stability. Her mother left school in Mexico City as a young teen to help her newly single mother support the family. When she met and married Claudia’s father, an accountant from Tijuana, they moved to LA county, where Claudia was born. After first working on a factory line, her father was quickly promoted to plant manager, and he ultimately invested in and ran his own factory with a handful of partners. Her mother was equally driven, founding a successful cleaning business, but she deeply regretted her lack of schooling, and the bruises on her life persisted.

Those early years were hard and lean at times, with some of the tumult and disconnect that’s common in any family where one generation’s circumstances are vastly different than the next’s. “I wasn’t a very good person growing up,” Claudia says a bit sheepishly, describing herself formerly judgemental, prone to categorizing and rating others’ behaviors, even trivial ones. She credits her children with the process of releasing that knee-jerk critical urge and going with the flow, with learning to practice what she had been preaching.

She’s such a good conversationalist today, able to talk to anyone about just about anything, that her assessment of herself feels like it might be unfair judgment in itself. A highly discriminating eye capable of making fine distinctions between this state and that, after all, is critical to her skills now.

Trying to find the thread running through her life, I ask whether there are commonalities between her parents’ Mexican culture and Chinese medicine. The answer? No…and yes. Her parents adapted quickly here “because they had to”, and she didn’t grow up with much brujeria or herbal remedies. “Vapo rub – yes. Yerba buena – yes. Don’t go outside with no shoes, or with your hair wet. There is a hot/cold thing.” And there was the concept of what we allow into our lives and our bodies having natural consequences. Still, a Chinese household with a Daoist framework might understand a lot better, she says, when it’s common to hear that a person’s heart Qi is disturbed. “But someone from here? They don’t understand why I tell them to stop drinking ice water.”

east/west

She started to question the standard medical approach via her own suffering. The only thing she was offered for chronic, severe back pain was prescription muscle relaxants, which she didn’t feel comfortable taking long-term, and things weren’t getting better. A friend suggested she try acupuncture. “Five treatments,” she says, “and it was gone.” After tiring of her OR career, she had been thinking of medical or PA school, but eyes suddenly opened, she applied to the AOMA Graduate School of Integrative Medicine for a doctorate in Traditional Chinese Medicine. “My family was fine with it,” she says, “but everybody I worked with judged my decision to go on this path.”

She still values her Western medicine training because it’s adept at addressing acute problems, like cancer or a heart attack; but, just as she refers patients who can’t be best served by acupuncture and herbs back to primary care or specialists, she wishes MDs could think more broadly, too. She tells a story about treating a man who developed new knee pain after back surgery, but whose doctor diagnosed it as totally separate. To Claudia, it was obviously a chain of events only treatable if understood in that way, as though the back and the knee had a common root. “I think there might be something behind childhood trauma and autoimmune disease, too” she says, wishing lab results and pharmaceuticals weren’t the only tools in the toolbox. “That takes people’s power away. They’re not encouraged to say ‘This is why it happened.’ What if the person did some trauma therapy, something to rewire that plasticity? It’s all related.” When that isn’t honored and addressed, she says, the patients end up frustrated. Sometimes a patient wants to heal so they can reduce the number of medications they need. Sometimes lab values improve on paper, but the person still feels ill, and they seek alternative care the way she did herself.

That word she uses, “rewire”, explains something about how she has a foot on both sides of what many of us would view as an incompatible divide. “When I say energy, to me it’s the nervous system. We do have positive-negative polarity in our cells. There’s something we can’t see, like radio waves or sound.” Some people around her call it the devil, and other people call it disease. To her, it’s just energy imbalance.

It wasn’t immediately natural to Claudia to think about people as just one element in systems working around and through them, in terms that are loaded with mystic meaning from a Western perspective. “In the beginning, I did feel the conflict,” she says. “Wait, when the moon comes up what happens? You replenish your yin? What?” But, the more she learned, the more the Chinese paradigm nestled into her own instincts about taking care with how we treat our bodies: sleeping, eating, and exercise are tied to circadian rhythms cycling with day and night, minerals and nutrients have known physical effects, movements open circulation and invigorate nerves. It’s not supernatural. “I like to think of Qi as one cell signaling the next, and the next, and so on,” says Claudia. “Qi is always flowing. In Chinese medicine, we say it becomes ‘stagnant’ with injury or stress, but that just means that it moves a bit slower – still flowing, just not as freely as it should.”

The biggest thing she wishes she could explain to people? “That I’m not stupid,” she laughs. Even though she thinks there’s no harm in a little astrological sign fun, she finds it frustrating that so few people understand what she does as a clinician, bristling at her work being lumped in with pseudoscience, indiscriminate supplement overload, and snake oil. Claudia’s program took six years, requiring chemistry, biology, anatomy, statistics, many hours of supervised practice, clinical research, and even instruction from Western medical doctors, so that practitioners can learn to spot acute problems. Given that, it’s irksome that some other practitioners assume they can provide the same services after a weekend workshop training, or no training at all, and the devaluing isn’t just theoretical. If Claudia has regrets about the career she chose, it’s that she makes a lot less than she could in a doctor’s office. Insurance will often reimburse a physical therapist with little experience – at a higher rate – and that means patients also get the short shrift.

It’s hard, too, when those patients expect a magic potion. “The difference between my herbalism and a random supplements store is that I’m looking at your overall health, and whether your liver and kidneys are functioning. There are too many ‘coaches’ who don’t talk about that. My stuff is medicinal. It tastes like crap, there’s no honey in it. If they don’t notice anything in two weeks, they want to stop. They don’t always do their part.”

art/science

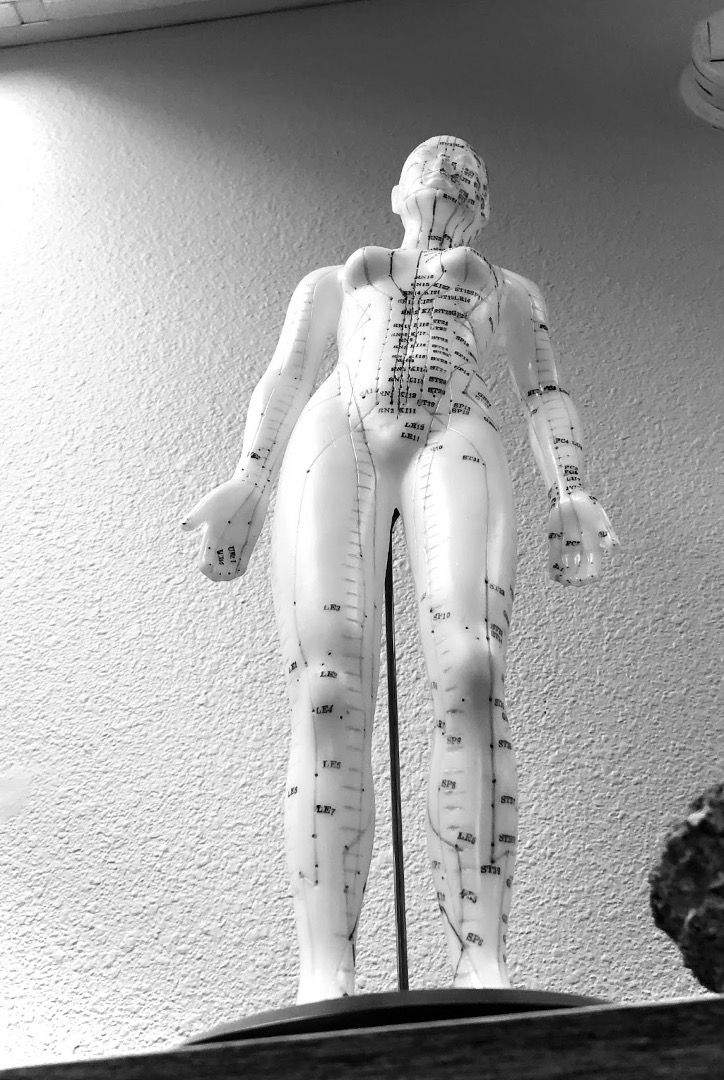

What’s different about Claudia, after her years of reflection and training at the crossroads? She has developed the gift of curiosity without the curse of ego. As she talks about how she treats patients, she is assessing the whole picture: diet, lab values, stress, family history, chemical exposures. As opposed to Western medicine, where something like her old back pain may have a single standard treatment, Claudia has learned that “you can treat two different people with the same problem from two different angles.” At first, admittedly, she zooms in, perhaps treating that muscle spasm with needles, and she calls that a science. “There has been imaging that reveals acupuncture points have a higher density of micro-vessels and contain a large amount of involuted microvascular structures,” she says, and that accounts for their capacity to influence nervous system activity.

Once that is done comes what she found lacking in her allopathic career, the part she defines as “the art of knowing what you’re looking at”: zooming out to study the underlying reasons the muscles seized in the first place. Is it a mom carrying a baby on one side as she does other tasks, harried, on too little sleep? Maybe that’s kidney Qi. Is it a veteran, repetitive physical stress with lifting, crummy diet, history of chemical exposures? Maybe that’s Yin deficiency. “I do believe there are fields. It’s not like I can fix everything, but I can read energy, sense where they have pain,” she goes on. “I’m not afraid of being wrong, though. I always say ‘maybe’ because I don’t know.”

the whole works

How are all of these spheres embodied and reconciled in a single person? Simple: her understanding of the universe, of Qi or of cellular biology, is deeper than either framework’s ability to describe it. Whether she’s explaining one side or the other, she’s always translating her actual understanding into words, and she’s choosing them not based on which side she believes is truest, but on which will reach the person she’s talking to. “When I say a person has ‘dampness’, I explain the Chinese view, but I use Western terms like spleen, kidneys, and fluids, to help them understand the context.”

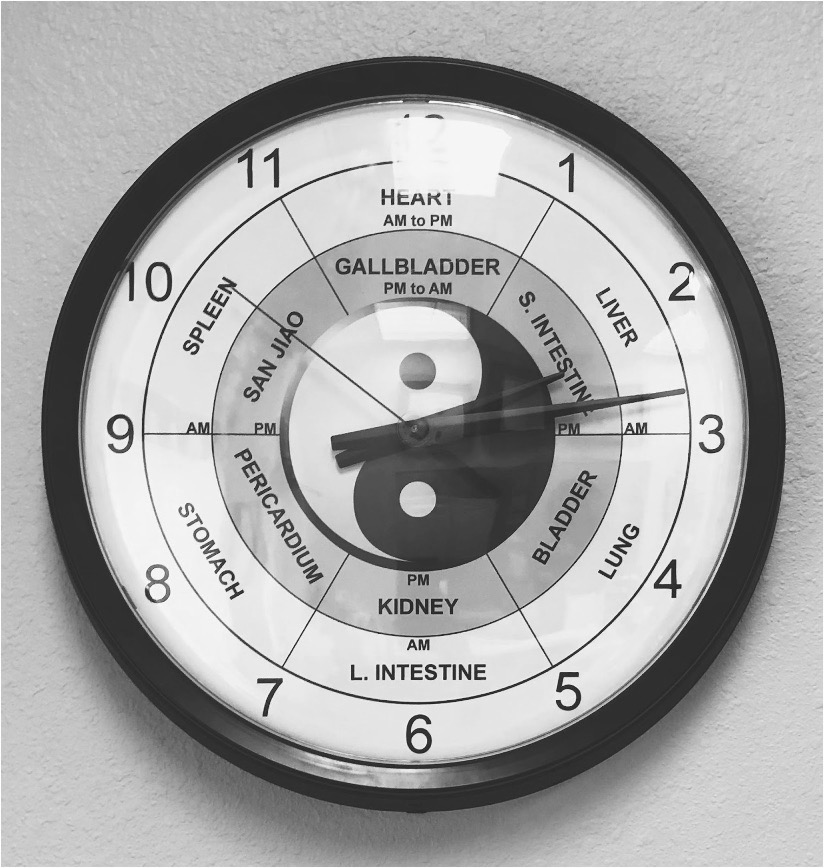

Most of the time, even in a healthy state, “perfect” balance is just a bit imperfect – but only in that it’s gently swaying to and fro around a happy medium. “Everything around has Qi and is in a constant state of motion,” Claudia explains. “That yin and yang symbol – it’s a perfect balance between the light and dark which is always interchanging. That is the goal.” It’s only in disease states where the tipping points between fire and water, love and fear, are far exceeded, and that’s where Claudia’s finely tuned eye of unprejudiced discrimination finds its purpose.

“At first I was translating even for myself, to understand it and justify it,” she says. “Now, to me, it’s all about energy flow. There are energies, things we can’t see.” She takes pains to explain that she’s not talking about living in a demon-haunted world of ghosts and lucky charms, but things with physical properties as scientific as they are mysterious, like magnetism and electricity. There’s no actual contradiction between art and science, just as the knee isn’t disconnected from the back, and just as the heart isn’t in competition with the mind.

Her main point, if she could explain it to the rest of us trying to make sense of illness and health, joy and sorrow? It’s that there isn’t one. “The balance doesn’t just apply to one thing,” says Claudia. “It’s everything. There’s only one system.”

Heather Martin is a registered dietitian in clinical practice, and a lay-entrusted Soto Zen teacher. She is also a freelance writer and Candy Corn Science Correspondent for several online publications. You can read more from her at her blog and Substack, or find her on Post and Instagram as @momofnorank. She encourages you to encourage yourself, and to take good care of your heart.

All photos also by Heather Martin, except for the final photo which was provided by Claudia.