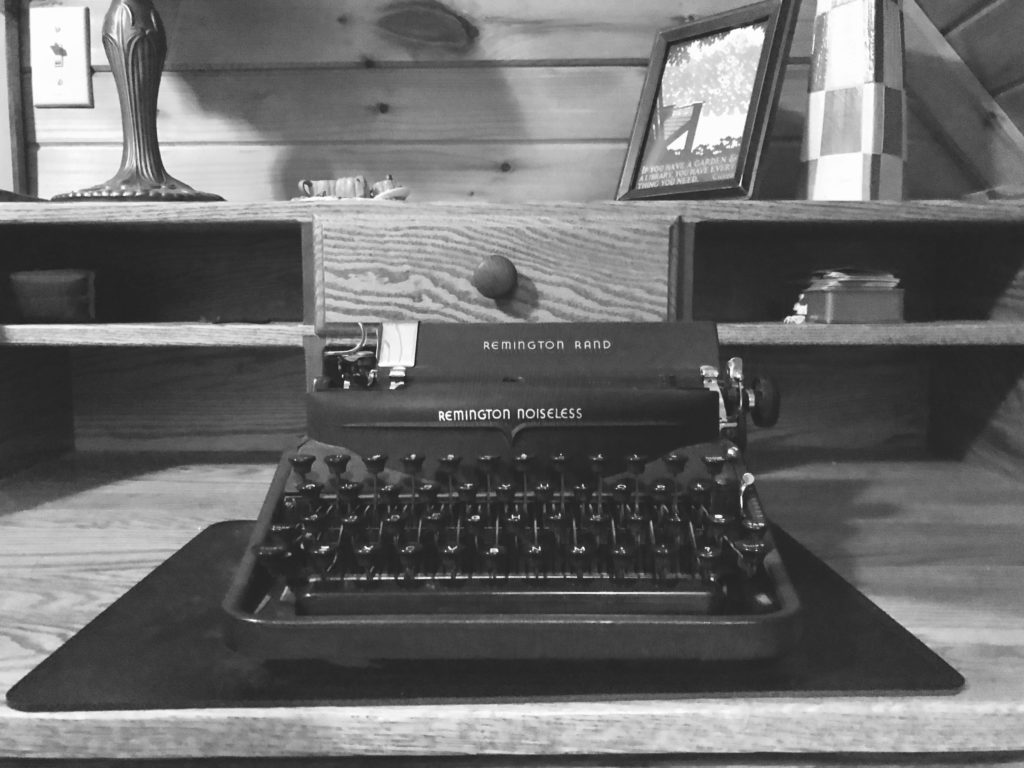

I sat down at a typewriter for this one, which seemed apropos. I needed to escape the expectations of today.

The orientation of the Remington keys, the monotone movement and expected carriage return when the rhythm called for a new line of text were a bit more my pace. I’m on my 39th carriage return, preparing for another decade of becoming. But before I arrive there, a little reflection on my four decades in the rearview.

Those first twenty years of my life were marked by A’s and 4.0s and myriad activities. I tried them all on for size – piano, ballet, choir, French Horn, soccer, cross country. And even lazy days at the beach. I marvel still at my privilege in being in a position to “do it all” and the graciousness of my parents to champion my interests. Yet in the swirl of constantly “going”, I discovered expectations I was all too ready to shed.

So I did what any overly committed young woman would do: I set my sights on the great West. I arrived at my “decade of widening” in the Bay Area, coming into open space and perhaps more into myself: pastries at Cafe Trieste; Beatnik poetry; eucalyptus-baked trail runs; peaceful protests; long days commuting to and from The Farm, soaking in views of rolling fog over the Santa Cruz mountains; manual shift parallel parking in reverse on the steepest of hills (for which I would have definitely been granted an expected A+). But the golden sun couldn’t keep me.

Family is paramount in my world, and my husband and I opted to return to the Midwest to cultivate our own. But that didn’t come with ease. Months of trying to get pregnant turned into years. I suffered a miscarriage on a friend’s couch. Talk about mortification, save only the grace of my God-given friend.

I poured myself into my professional pursuits, birthing instead an organization – Allow Good – that prepared youth to become civic agents of change in their own communities. Allow Good, to me, was a garden of learning cultivated in service to the community, to the world. Krista Tippet, On Being’s curator extraordinaire, offers this view of our work in the world, which resonates deeply with me:

“Somewhere along the way in this culture a person’s vocation became synonymous with their job title, but I think of vocation as the full range of our callings as human beings. Yes, as professional people but also as family members and neighbors, parents and friends, and members of a body politic. Vocation is not so much about goals and accomplishments. It’s about how we orient our lives and our attention and our passions. At different stages in life, different callings emerge and take primacy — what we focus on and pay homage to with our presence, and what we fight for from the ground of what we love.”

I sank into my vocation.

And then I got pregnant, and he stuck. Was he ever worth it. Three and half years after he graced our lives came our next little miracle boy. I stashed away my PCOS woes, buried them deeply as generativity for my children became chief instead. But do we ever really dismiss all of our pain permanently? Can self forgiveness truly reign over that which tears at the fabric of our identity? In all the rich goodness I was experiencing as a mother, wasn’t I still holding on to insurmountable expectations of myself? How would I emerge?

At dinner the other night, my three-year old asked me, “Mom, when you close your eyes, do you see the universe?” In his question, I emerged.

Oh yes, and it looks like this…

A whistling copper tea kettle preparing lavender honey and lemon water perfection.

Snowy dune runs ending in visceral elation.

Discovering an unexpected, handwritten letter in my mailbox on a Tuesday afternoon.

Sun-baked children at dusk, dancing sparklers on the Lake Michigan coast.

5,039 mile-long video calls sending signals to Kyiv, bouncing back images of my gleeful nephew.

Peonies at their prime, their exquisite bloom centering us as we gather for a meal.

A cacophony of kinders piled in my backyard. Intrepid children.

Perfectly wrinkled parents, primed with purpose and marked by loyalty and grace.

A crackling fire and Mary Oliver’s Home on a snowy winter’s eve, weighty pine boughs out my window.

A slow dance with my lover beneath our crystal chandelier.

My tiny universe.

How have my life’s markings – but an integral interlude between dusty, earth-bound bookends – been received? To standing ovations or quiet contemplation? Would either be enough?

His question about the universe – in what has been a very different kind of year – revealed to me a truth: I am enough in my one, sacred life. A year when a global pandemic, the wrestling with racial injustice, and an uncertain economy reared her head, I just happened to be preparing for my own fourth decade. Seems pretty trivial amidst this backdrop, no? Prehistorically, “four” signaled solidity, wholeness, and universality. If this is the promise, I’m ready to leave the precipice to meet that sacred, sturdy ground.

In a recent graduate school course, I was introduced to “liminality”, an anthropological orientation derived from the Latin word limen, meaning “threshold”. Liminality is marked by ambiguity and disorientation, and it appears in the middle of a rite of passage. (I’m looking at you, age 40.) But, so too, is it an invitation to becoming. Thus the resonance with me at this particular moment in what I only pray is at least a middle marker of my earthly years.

Becoming happens in all forms. I recently traversed the Camp Wokanda trails in rural Illinois alongside my chosen family of in-laws. Surrounded by farmland, I was awed by the rolling topography, glacial remnants of centuries past. Just a handful of minutes into a hike we found ourselves beneath a web of lines stretched among the trees. “A low ropes course!” I shouted with youthful glee, emblematic of my childhood days when we swung from ropes and branches in trust falls and spiderwebs of team-building exercises. But as we drew nearer, it dawned on me. This wasn’t a winding web of ropes but frosty-blue tubes tethered tree to tree as if intricately and exquisitely stabilizing one to the next. Sap moved at a sticky, liquid pace through the translucent tubes. Each tap captured sap in slightly tilted tubes from the forest canopy to floor. I stood in amazement. How had I, a Michigan girl, never witnessed such simple, syrup-collecting beauty? Remember the momentary disorientation of liminality? This is becoming.

This visceral vessel

of motherhood exposes – with sheer audacity – me.

I see eternity, as he sees it: “Eternity between two beats of the heart”1

The trilogy of body, soul, and mind stand naked and

close to the ground and alive as the impossible limits of the sky.

The fragility of nature knows no bounds. Nor do I.

Smashed in middle management.

Betwixt juggles of cultivating children, professional

pandering, and parental pacification, I glimpse another trifecta.

A cycle of discernment reveals this “half” mark

is a hallmark.

It is okay to have been me.2

Nature’s becoming reminds us – in pure reverence – of our own human transfiguration. Where I redefine myself from “professional working mom attempting to juggle with grace” to “woman on the edge of her fourth decade, enraptured by becoming.” In the crowded forest, there I am. Emerging. Coming home and sinking into my one, sacred life.

1William Blake

2Referencing: “Is it okay to have been me?” – Erik Erikson, “Identity and the Life Cycle” 1959

Elizabeth works as an independent philanthropic advisor serving individuals, nonprofit clients, and family and community foundations. She also founded and led Allow Good, a social purpose organization dedicated to elevating next generation philanthropic learning. The Allow Good curriculum is cited in myriad next generation philanthropic forums, including Northern Trust, Learning to Give, 21/64, and LAAF.org. Early in her career, Elizabeth spent nearly a decade creating and leading social and global impact programs at the Stanford Graduate School of Business. She earned her master’s degree in International Comparative Education from Stanford University and undergraduate degree in Spanish and Business Studies from Butler University. An avid outdoor adventurer, Elizabeth relishes time distance running, Nordic skiing, and hiking with her beloved husband and two boys. In 2005, she summited Mt. Shasta, the second-highest peak in the Cascades, with a group of 8 other women from Stanford.

photo credit: also Elizabeth Newton