Water flows downhill. Everybody knows that.

It condenses and falls from the sky, gathers into rivulets and streams, then raging channels, and finally the open ocean, where it returns to the air in time. It’s predictable, dependable, an assurance that the world works according to the rules.

In certain circumstances, though, when conditions are just so, water doesn’t flow at all; a field of snow can flip molecules like a switch, solid to gas, sublimating ice directly to vapor and skipping the liquid step entirely. To the casual observer, it might look like magic at best, turning one thing into an entirely unrelated thing with a supernatural flick of the wrist. At worst, you might mistake it for cheating the laws of physics, skipping a fundamental step, overturning the universe.

It’s exactly at that point of tension where you’ll find artist Fernanda Martinez. Whether a canvas, a tote bag, or a three-story wall, her style is immediately recognizable. Stand close, and organic shapes like torn paper or the river’s edge would hint at a fall to chaos but for the repeating chorus of blues and greens, scarlet and canary. Hold back, and you’ll see pillars, waves, leaves, shadows, or even a window, the secret garden looking in on itself. That’s a gift many an artist would sell their soul for, but it came to Fernanda in a way that might be hard to understand, when you think you know the way the art world works.

You could dismiss her as untrained, an amateur, but you’d be poorer for it. It’s true that growing up, there was no thought of art school, much less becoming a professional artist. She describes her native Mexico as “rich in nature and culture”, but family expectations – every parent’s practical exhortations to be successful, to pay your own bills – led Fernanda to study communications in college. “If here it’s very, very difficult to be an artist, in Mexico, it’s double-difficult.”

Art was not in her plans at all.

After studying communications in Mexico City, Fernanda married and moved to the Bay Area in 2015, for a business management degree. Sales came naturally. “I think I had probably three different businesses growing up when I was not even finished in school,” she says, describing jewelry, fashion, and photography pursuits.

When she graduated and a sales job didn’t appear, she started designing home goods – stationery, fabric, tote bags – to sell for income, finding that she enjoyed infusing joy into things people interacted with in their daily lives. She called her tiny company La Tinta, Spanish for “ink”, and started making connections at art fairs and markets. Her art was a side hustle, with a detailed, illustrative style to engender product sales. ”I painted a lot of plants and florals, different landscapes or scenes from…I think memories…but also, situations or spaces that I found interesting. I just wanted to explore with different mediums because I never had the opportunity to go to art school. That’s something that I realize now would have been amazing, actually pursuing that path, but I don’t know,” she says, “it was probably by accident that I started painting and experimenting.”

I hear her saying that, but to me, it sounds more like a foregone conclusion. The little handholds in creativity for the businesses she chose are the other half of her inheritance. Her mother took Fernanda and her brother along to art classes at a local college when they were kids – she had a secret wish to be an architect, but died young. Some of her mother’s landscapes still hang in her family home in Mexico. You could say the artistic side of her product sales was an afterthought, just a backdrop, but maybe it’s more likely it was the foundation, in her blood.

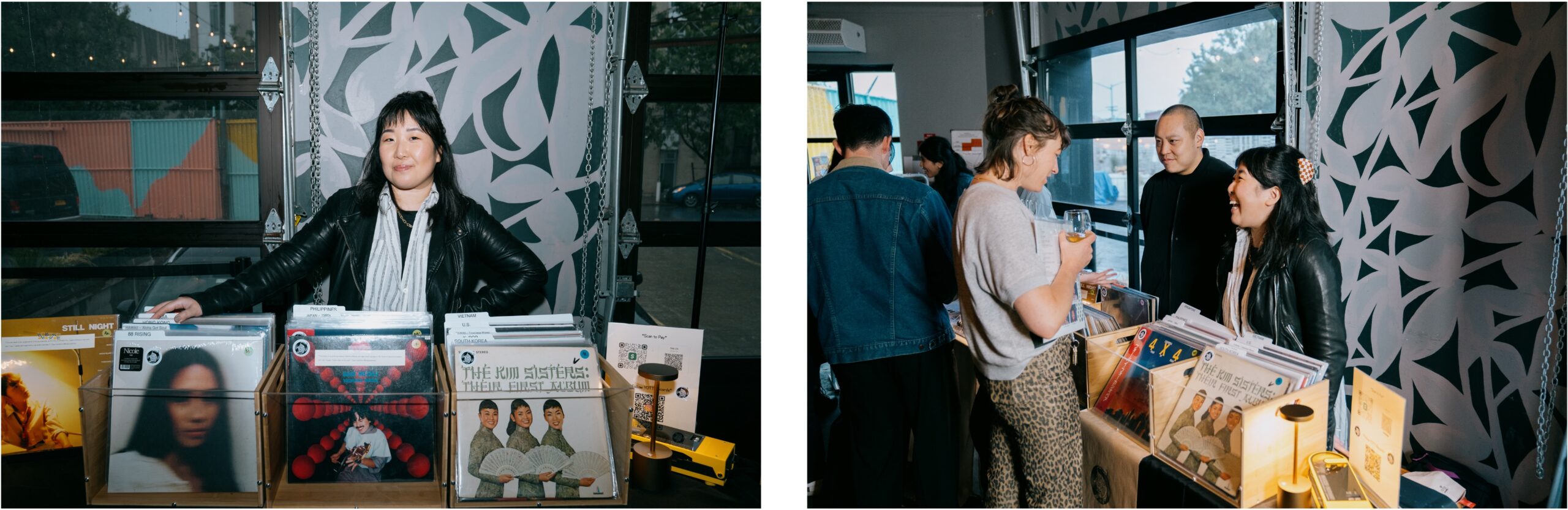

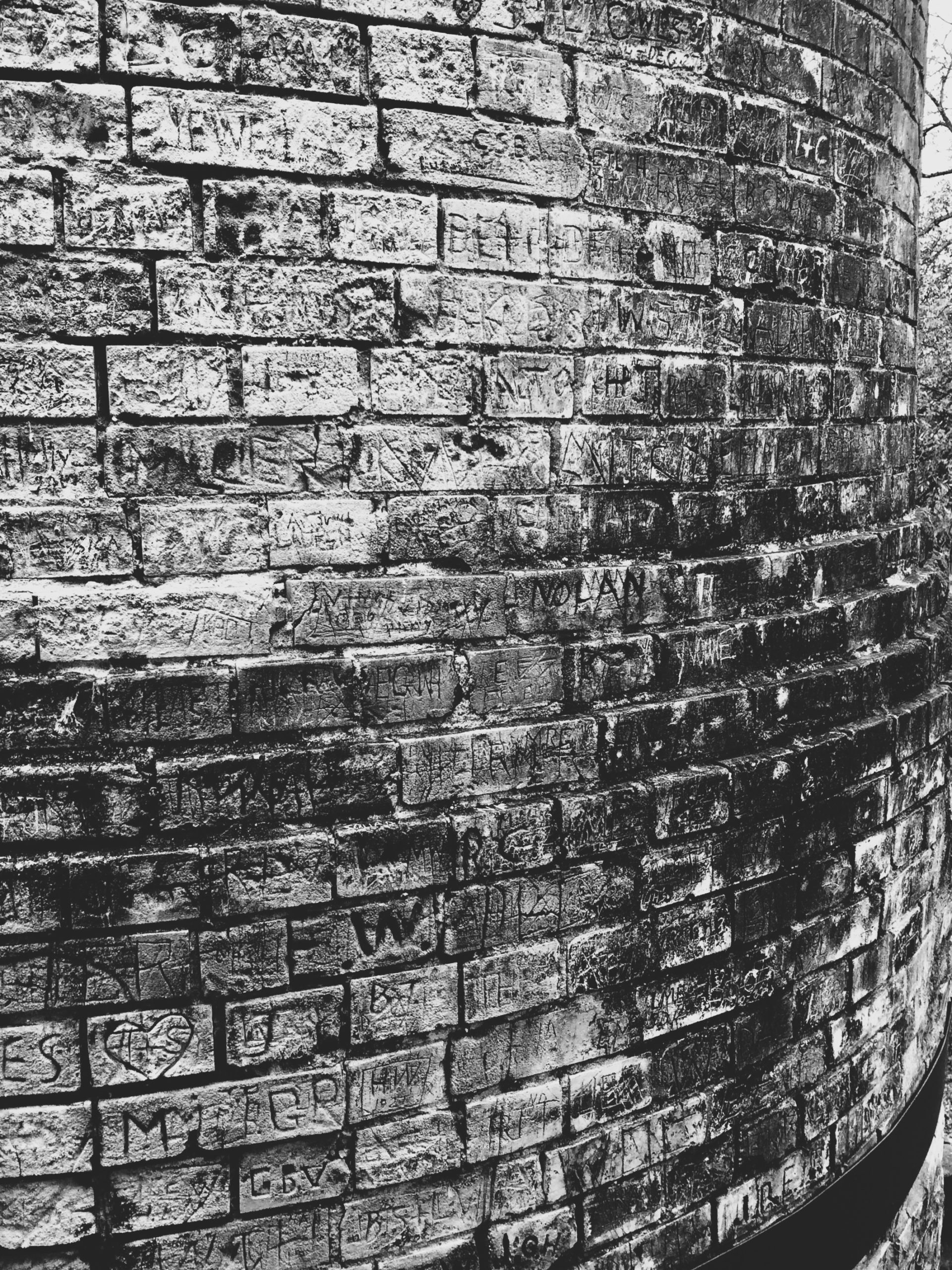

Before long, her brand grew, and she had collaboration deals with Anthropologie, Atlas Edibles, and World Market for labels, stationery, and decor. Then, she came to a wall – specifically, the interior wall of a friend’s San Francisco office – painting a jubilant explosion of brightly colored blobs and splashes for a gaming company. From there, she began painting murals on exterior walls of shops that already sold her goods, and she found a support system of artists who were incredibly generous with their time and advice on materials. “From the beginning, I knew community would be crucial to my development,” she says, explaining that she didn’t even know what kind of paint to buy, much less how much of it, and she’s grateful for the support she continues to receive from other muralists and graffiti artists.

As she explains her workflow for that physically demanding task, my jaw drops when I understand what she’s saying. “Wait, you just draw on the building?” I ask. “Yeah, I just freehand it,” she answers casually, as though it’s a small detail, explaining that when it’s projected and traced, it doesn’t feel natural to her.

Once she did one, it snowballed. “It was funny because the store across the street saw my mural, and they said, well, we want a mural too. So, I went there, and I painted one for them, and then another business owner in the same street saw both murals and she was like, well, I want a mural as well!”

Why murals? It seems like a huge shift, from a notebook cover to a three-story building, until I hear Fernanda talk about her artistic motivations. She understands well how community has benefited her, and she’s looking to make it flow back to the people around her. “I have worked on multiple projects, community-oriented projects and affordable housing,” she says, “and I now see the real impact of these art installations in these spaces. You’re able to bring new possibilities to see the world differently in these very hectic communities and very hectic world. Because, these details are very easy to lose – you don’t have the time or the energy to look into art when you’re worried about something or have other needs, other priorities.” When people in a neighborhood see public funds devoted to the beautification and interest of their spaces, she says, it can have far-reaching effects. “You feel like they are investing in you, and that really changes the way people see the world, and how they go into their lives every day. If somebody’s walking down the street, when it’s decorated, that means their neighborhood has value, just like if the fabric or the notebook is decorated, that means it has value.”

The value that Fernanda is offering has a lot of layers, and this is where it gets interesting. Many of her early murals and illustrations are unapologetically botanical, vibrantly natural colors, repeating tiles of tessellated stems and fruit. They look like what they are. Her emerging fine art style, though, has its own life, and it’s otherworldly, depicting inner lives as much as the world outside. “I want people to look in and see details,” she says, “ and really ask themselves, ‘What am I seeing? What is the shape?’ l don’t want them to see the pieces and think, ‘Oh, it’s plants,’ because it’s not only plants!”

I ask whether she has something in mind when she paints but is making it purposefully vague? “I can’t answer that,” she says, smiling, “If you’re not able to describe what shape that is, that’s a good thing, because I don’t even know what it is.”

“…and I really enjoy when people don’t know what it is.”

Despite her own assertion that it’s a futile enterprise, you could be forgiven for staring at Fernanda’s work for a long while, trying to figure it out; I started out that way myself. What is she portraying, I wondered? Is she painting the plants she saw growing up, the ones in her home? A snorkel dive? Shadows on the sidewalk?

It finally dawned on me that in the same way ice into vapor isn’t magic, but a process, her work is a verb instead of a noun. It’s the instantaneous, mystical process of sublimation expanded into days and weeks, molecules opened out into oversized dioramas, visible to the naked eye through her hands. Once you’ve absorbed the lines and colors of her paintings, one key to understanding might be to read the titles: Hold Your Ground, Would you resist, Majesty, Wandering Around.

Fernanda describes these words and phrases as the handles she puts on the piece when it’s done. For her, they index what she was thinking, seeing, hearing while painting that canvas. “I like to title pieces depending on the meaning of it to me, or if I find a clear narrative that I want to point out,” she told me. She’s looking for something “short and impactful”, and it might be a song lyric, or a simple story of the work, like “Lost but found”, a canvas once forgotten and then finished weeks later.

One work took so long that the process became overtly primary to its meaning to Fernanda. “I knew the title had to be related to the process of it. When the piece was finished, I read ‘Things will unfold’ somewhere,” she says, and she found echoes of the composition itself – “Some elements are separated by hard edges that make it look as if it will unfold literally,” she notes – but also the creative block she had labored to make her way through.

As big as her murals are, she’s turning her eye to public works sculpture next, and now business is the side hustle turned critical component. Fernanda estimates that the administrative part, marketing your portfolio, applying for grants and projects, making connections, is half of her time. “It’s interesting because now I realize that all that business experience, even though it was a short experience, really paid off, because I was used to working with a lot of business owners and I was also training people, so I know how to talk to people in general.” The public works field is incredibly competitive, especially for abstract art, but that’s where her interest is at present, and “I know it’s going to come,” she says. From the way she talks about how she sees the world, I have to agree it seems likely. “I really enjoy seeing different lights and shadows, and how the materials relate to each other, and how even though concrete is a very rough and a very hard material, it is soft, it kind of looks soft when the sun hits really hard on concrete, almost like it’s going to melt. The same as metal.” Surely it’s only a matter of time before the rest of the world wants to take that kind of vision for a spin.

Where business and art meet and blend like light and shadows, she’s still trying to find the fulcrum of her life’s work. “I guess it’s a balance,” says Fernanda, “I”m trying to see what’s important, because some of the big projects are going to pay my bills for the year, but they take a lot of time.” That time spent on a ladder painting a wall means less time in the studio.

One of the things that tips that balance is the social expectation that we all constantly create new content, adding updates to the website, new photos, multiple unrelated projects. “That’s very contrary to the way it has to be [as an artist],” Fernanda maintains, “where you sit with the piece, you sit with the process, and you might create 40 paintings, but you only show 20, because the other 20 are trash. I’m trying to create this way of working that is very different from the social norm.”

I asked Fernanda if there’s anything that came to her in thinking of her own life as we talked about it for this profile, and she touched on a point that everyone creating at a crossroads seems to, eventually. “For a long time I tried to divide my mural work from the fine art work,” she admits. “I had this idea that I was not going to be taken seriously as an artist if I kept working as a muralist.” She worried that the prominence of her building-sized works on her website and Instagram would hold her back, but finally, she says, “I just got into the point that I just think it’s part of me. I can’t divide it. People know me because of my murals – that’s true. I can’t fight it, and there are a lot of artists who do murals and also work with galleries. I think it’s actually beneficial to do both.”

That pressure to choose a side, to flip to the right one – art or business, solid or gas – is an illusion. Sublimation only looks like slight of hand if you don’t understand the true nature of water. Study it deeply, and you come to understand it’s actually proof of a unified reality, and not its undoing. Fernanda’s artistic mind and head for business are the same way, two ends of the same candle, each burning bright.

The only way to hold it and still keep it lit? With both hands, right in the middle.

Heather Martin is a registered dietitian in clinical practice, and a lay-entrusted Soto Zen teacher. She is also a freelance writer and Candy Corn Science Correspondent for several online publications. You can read more from her at her blog and Substack, or find her on Post and Instagram as @momofnorank. She encourages you to encourage yourself, and to take good care of your heart.

Lead photo by Kathy Yang.

Painting image by Fernanda.

All other photos by Jess Mutya.